Choosing Channels for Your Personal Mixing System

Channel selection is one of the most important—and most overlooked—factors in implementing a really successful personal mixing system.

Let’s start with a fundamental premise: musicians and engineers are different. They have different skills. They have different needs.

True but why does that matter? Well, from an engineer’s perspective, having more channels is almost always a good thing: more channels means more control over the mix. It’s like getting the box of 64 crayons instead of just the basic eight or 16. It’s why it’s not unusual for an engineer to mic both the top head and the bottom head of the snare or to take the bass in direct and by miking the cabinet: those added inputs give the engineer more ability to color the sound the way he or she wants, and that’s one of the things good engineers do well.

The Musician’s View

But most musicians wouldn’t know what to do with those extra inputs, and even if they did, managing those extra channels requires time and focus that the musician should be devoting to the music itself and not mixing.

For musicians, mixing should be a means to an end (they’re trying to get the right monitor mix so they can play better), but for an engineer, mixing is the end. So every channel in a personal mixing system comes with a small cost to the musician: it’s one more thing to manage while focusing on playing great music.

For musicians, mixing should be a means to an end (they’re trying to get the right monitor mix so they can play better), but for an engineer, mixing is the end. So every channel in a personal mixing system comes with a small cost to the musician: it’s one more thing to manage while focusing on playing great music.

So when you’re looking at choosing channels for the musicians to control in their monitor mix, a good starting point is to ask “What do the musicians need to adjust?” Or “What are they always asking the engineer to adjust?” Chances are good they’ll be asking for things like vocals, bass, the guitars, drums, and maybe something more specific like kick drum or snare. Chances are low you’ll ever hear a musician asking for more or less top snare!

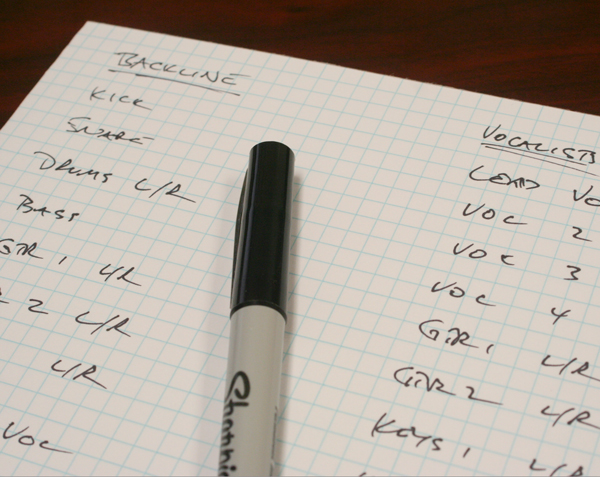

A typical input list for a personal mixing system for an ensemble with pretty standard rock band style instrumentation would include the following channels: individual vocal mics, individual guitars, bass, keyboards (ideally in stereo!), and a stereo mix of the drums, sometimes supplemented with individual channels for the kick and snare so those musicians who like a lot of kick and snare (drummers and bassists) can make that adjustment. That approach keeps things reasonably simple for the musicians and allows them to rely on the engineer(s) to do the more involved mixing required for making a good drums submix. Remember that most musicians will look to adjust “the drums” and not, say, the second tom or the overheads and so on. So you don’t need individual control of those channels in the monitor system, and providing that level of granularity would simply be a distraction for most musicians.

Different Channels for Different Musicians

Different Channels for Different Musicians

The other factor to consider—especially in larger ensembles—is that different people in the band will likely want control over different things. For instance, musicians who aren’t also singing simply need to hear the vocals—especially the lead—so they know where they are in the song and to key off the phrasing in the vocal parts, but they don’t need control over each individual vocal channel. So they would be best served with a stereo mix of all of the vocal channels made by the engineer. The vocalists, however, need to be able to adjust their own vocal channel and so would be poorly served with a submix of the vocals.

One of the things the A360 Personal Mixer allows you to do is select the mix channels for each personal mixer independently, choosing from all the channels in your system (up to 64 of them). That means that everyone in the band can mix exactly what they want—lots of vocal channels for the vocalists, more drum channels for the backline, and so on. It’s a great way to give each musician exactly what they need in order to hear their best and play their best.

Additional Considerations

- For the best fidelity, especially if the musicians are using in-ear monitors or headphones, keep input sources in stereo if possible. Make sure all your submix channels are stereo as well. (We’ll do a future post on why stereo makes such a big difference.)

- If you use loops, tracks, or sequencers, send them as individual channels or a submix. You can also dedicate a channel to a music director’s or conductor’s talkback mic.

- If the musicians want to hear interaction with the audience or some of the general room sound, you can set up ambient mics and send a mix of them to the personal mixers. Note that the A360 has a special section of the user interface designed specifically for use with ambience mics.

- Some users send an output from the console’s effects section (or the outboard processor) to the personal mixing system. This allows musicians to control how wet their monitor mix is while still relying on the engineer to determine how much of each channel to send to the effects. (Note that the A360 has per-channel reverb on the mixer itself.)

The bottom line is that you want to keep things as simple as possible: give musicians the control they need, but don’t give them channels just because they’re there. This will allow musicians to dial in their monitor mix to perfection, make good mixes, and stay focused on the music.